THE PROJECT

The Mass/Cass History Project will use historical records and interviews to tell the story of a small but important Boston neighborhood from 2014 to 2024.

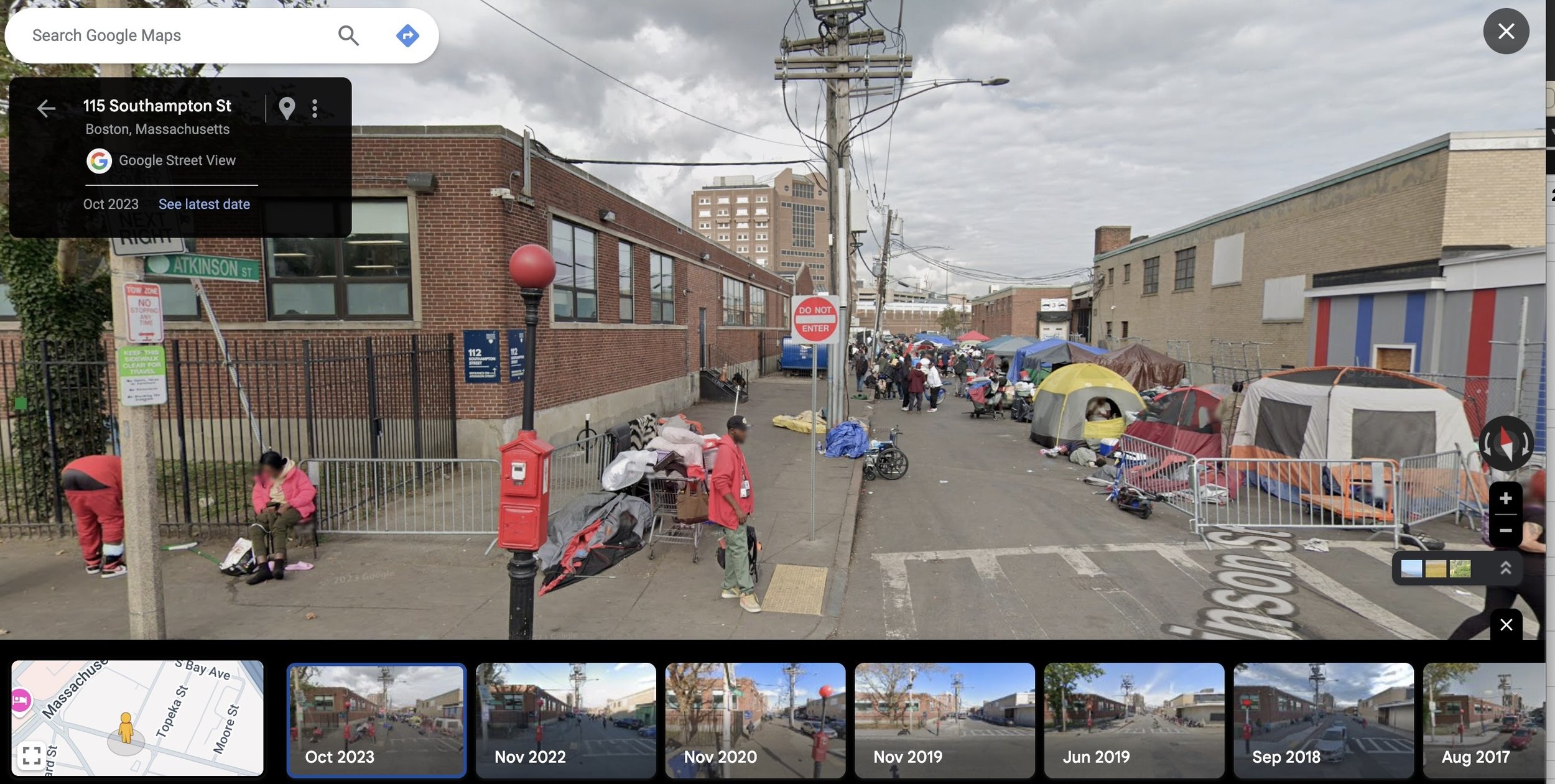

The area just south of the intersection of Massachusetts Avenue and Melnea Cass Boulevard became what some describe as a “containment zone”. It was an area where drug use and sales were more tolerated compared to other parts of the city. There were a lot of people there who stayed in shelters, or lived entirely on the street.

Many of the formal elements of the zone were ended in the fall of 2023. But that didn’t end homelessness, or drug use, or controversies about what to do next.

When I started working in this area as a doctor in early 2015, I spent most of my time thinking about medical things: overdoses, addiction, infections. But I’ve always also been interested in how cities work and how they evolve. So now I’m learning about urban planning, and learning so much more about Mass/Cass now that I look back on this story with new eyes.

To tell this story I need to talk to lots of people! I want to talk to:

People who were homeless, and stayed in shelters nearby, or lived on the streets in this area.

Police officers, healthcare workers, city workers, attorneys, correctional officers, or people who worked in other jobs in nearby businesses or organizations.

People who came to the area to buy or sell drugs, or knew a lot about the street economy of Mass/Cass during this time.

Residents of the area: people who rented or owned a home nearby; or spent time in the area in a halfway house or residential treatment program.

Family members of people who were down here.

Participants in neighborhood or political groups that were part of debates about this area.

And anyone else with a story to tell.

However you were part of this story, I want to talk with you.

I want to learn from you the story of how events in this area had an effect on your work or your life—whether positive, negative, or no effect at all. And also: how you had an effect on events in this area.

If you’re wondering about where I’m coming from, I’m glad to talk to you about that for as long as you like. I have a point of view (here’s a long explanation)—but:

My biggest point of view is that, although I had a small part in this story, I didn’t really understand it. Or at least, not as well as I will, when I talk to you.

I can just about guarantee you that I will talk with people who disagree with your point of view about this story, and probably others who agree. And that’s why I hope you will talk to me. Without many points of view, many stories, we can’t really understand the history of Mass/Cass. And until we do, other people can’t learn from it.

I’m glad to talk to you on the record, confidentially, or entirely “on background”, whatever you’re most comfortable with.

Top: The Engagement Center when it was still a tent. Middle: Historical Google street view of Atkinson Street. Bottom: From front to back, a Boston Public Health Commission police cruiser; trailers for public health workers; the later-stage brick-and-mortar Engagement Center; and the Suffolk County House of Correction.