* * *

For a long time, I’ve followed this idea of a career shaped by what I call “The Rule of Tears”. And the idea is that the things in your work that bring you tears, not like frustrated or grieving tears but more like just-saw-an-overwhelming-movie tears, just-heard-a-beautiful-piece-of-music tears—these are the things you should move towards.

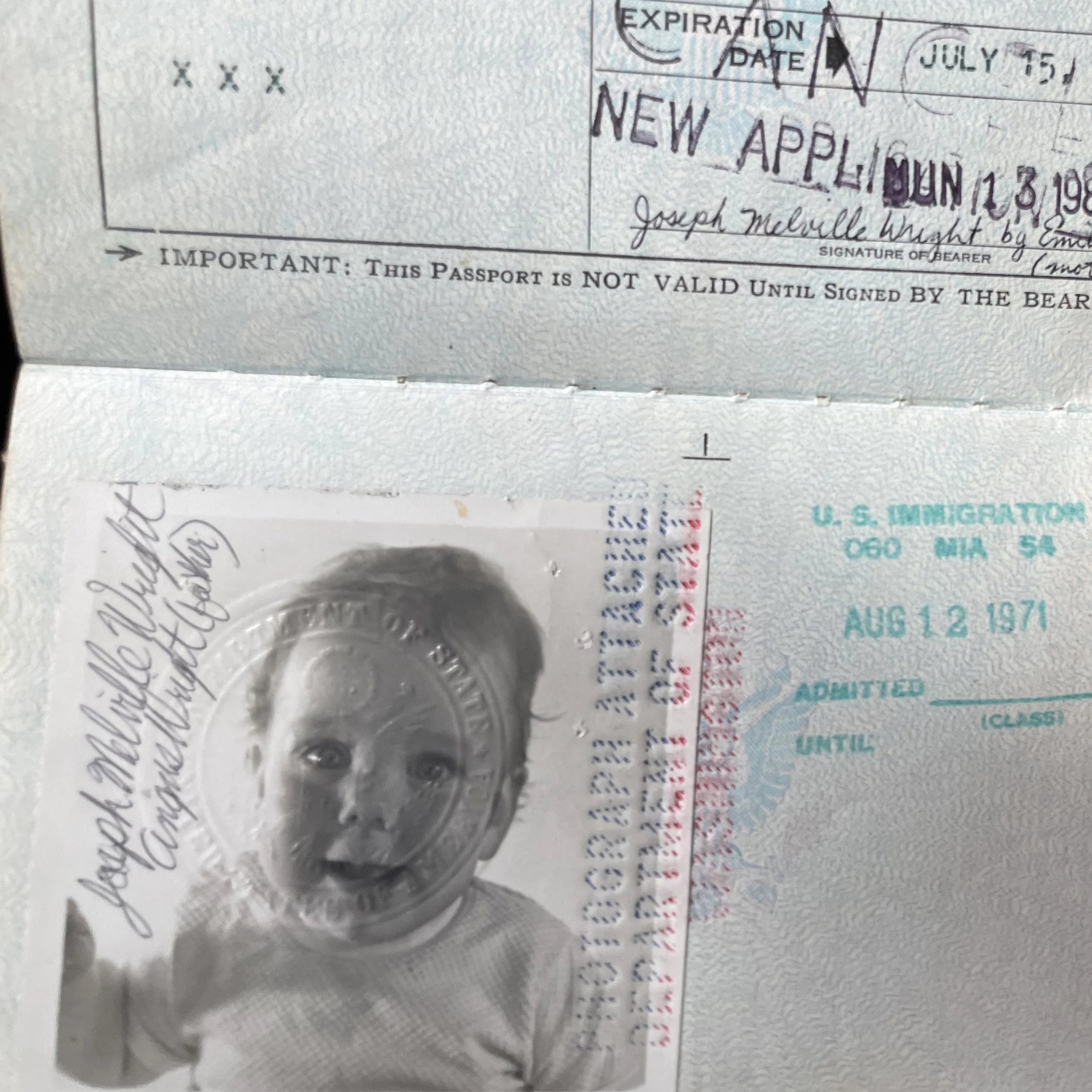

I still believe in that idea, at least partly. It’s what led me to HIV work and away from trying to make movies; towards medical school and away from applying to Ph.D. programs; and then what led me to leaving academic primary care to do addiction work among people without homes. It is an expression of a secular spiritual impulse; those tears come from a feeling of love, of connection, of beauty. Of fiercely shared common purpose. I found that feeling in the community of people fighting HIV; in needle exchange; in certain parts of medicine.

The Rule of Tears has taken me to good places, and then has led me to walk away from some of those places. When I’d started drifting away from the core thing that had brought me there. When it was time to find that somewhere else.

* * *

But as I get older, I also have added a kind of caution to the Rule of Tears. Sometimes a closely-related variety of tears come because my own feelings are obscure to me. In other words, when we’re overwhelmed with emotion, it might not be because the emotion is inherently more important than not-overwhelming emotions, but because we don’t have language to figure out what we’re feeling, the words and explanations we need to contain it.

It’s a feeling that is strong, remains undescribed, only poorly grasped if sometimes deeply felt, coming from underneath the surface and out into torrents from time to time. And that strong eruption of feeling is what makes you cry with it.

I’ve felt the tears of beauty and spiritual connection at all kinds of times, from listening to a house music record, to being part of a political demonstration. But the things I keep going towards are way way more full of tears, and there’s something about grief and trauma that keeps drawing me towards it. Are these the tears of beauty? Or is it just looking for pain?

Like I’ve said before, lots of people go into their particular field of medicine with a resolute intention to contain or even frankly avoid strong emotions, and some of them show up to work and do their jobs every day. And depending on the number-needed-to-treat of their particular intervention of choice, some of them may do more good in the world than I do.

For those who did go towards the pain: I think some of them go to fields like critical care; others to oncology; some palliative care; and still others in corners of medicine, like the one I’m in now, with problems that are driven by more social and political forms of trauma and despair. And, I sometimes think that if I had a different set of political impulses, but carried my same emotional hardware, I’d be a leukemia specialist somewhere, overhearing my resident on the phone to someone going, “Yeah, I’m on liquids, it’s so brutal, just a week of this left.” Whatever the board certification I ended up with, I’d still be in a place full of pain and drama, but also of shared purpose. Of a shared fight for life. But let me tell you about a fire, that should make you suspicious of going towards the pain.

* * *

Back a long time ago now, my girlfriend (now my wife) and I lived in an apartment building that was partly consumed by fire. We were out in the street, having lost our home. And it’s a story for another time, but getting out of the building was not a straightforward story. It was stressful and traumatic, especially as we were standing out on the street after it was all over, letting what just happened sink in. We were both medical residents, and we had supporters, and paychecks, and we were going to be able to deal with being without a home for a while; but still. It was shocking.

We were out on the street, and I remember our fierce little cat squirming around in her carrier bag that was slung around my wife’s shoulder, and then mine. We called our respective chief residents to tell them we weren’t going to be able to come in the next day. There were all these fire trucks, and the smell of smoke from the fire now being fully extinguished, and the old lady from upstairs had been taken off to the hospital, and we were trying to figure out what to do next.

A small group of Red Cross volunteers were going through some kind of disaster response inventory, and making us register for something before they would do something else for us. So, not knowing what we were going to do next, we registered, only to find that the something else they would do was in fact, nothing else. Probably they were perfectly nice, but our reaction was eventually: these people are useless. And yet they seemed full of a sense of the urgency and importance of their mission.

Of course, my wife, now a medical school professor somewhere respectable, doing respectable things, would surely never have said, with a bleak and definitive dismissal: “Those people get off on this.”

So it must’ve been me who said that.

Anyway, we’ve seen it in our colleagues, and recoiled from it whenever we started to see it in ourselves: going towards grief and pain for the wave of emotion it brings the observer. Medical ghouls looking for suffering, for the realness, for the intensity, for the drug of other people’s unsolvable pain. After standing there getting nothing useful from Red Cross volunteers who seemed to be inspired by their own feelings of sympathy for our pain, I think both of us have ever since looked at certain kinds of “medical humanism” with a deep suspicion. Because being there for people’s pain can stand right on the line of being either the noblest part of humans as social animals, or—

—it’s such a thin line—

just low-down vampire hunger.

Feeding off the intensity of other people’s circumstances is a way to substitute other people’s strong emotions, or the emotions they inspire, for our own emotional state. It allows clinicians to have strong feelings without having to feel our own experience, without having to delve into the complexities of our own circumstances and histories. We can feel a version of the pain itself, without the bitter notes like shame or guilt that accompany our own personal pain. Other people’s pain is simpler than our own. Shoot it into your veins: here comes the rush of realness, without having to feel your own real.

But the Rule of Tears does not have to lead towards pain. At its best, it has led me towards beauty. And the places of beauty, found amidst pain, are most often the places where my patients are at their most powerful, their most human, where I am genuinely humbled by them. It is not a coincidence that beauty-amidst-pain is usually the theme of the movies and the music and the art that makes me cry, what makes me hold a song closest to my heart. This is my wiring; and in my work, it is where my true gifts can best be found.

Of course—don’t tell me you’ve never seen this in a doctor!—a pose of humility can be the half-conscious sly prowl of an emotional parasite, oh, gosh, I’m so humbled by my patients, as I am becoming filled up with a feeling of significance—oh! shoot it into the vein! Gosh, thank you, dying person, for what you’ve given me today.

Sorry, although your home caught fire, I have actually provided you nothing of value, but I was here, when the firefighters were here, and I am now driving back home humbled by the awesome importance of what I just did, and thus, my own importance.

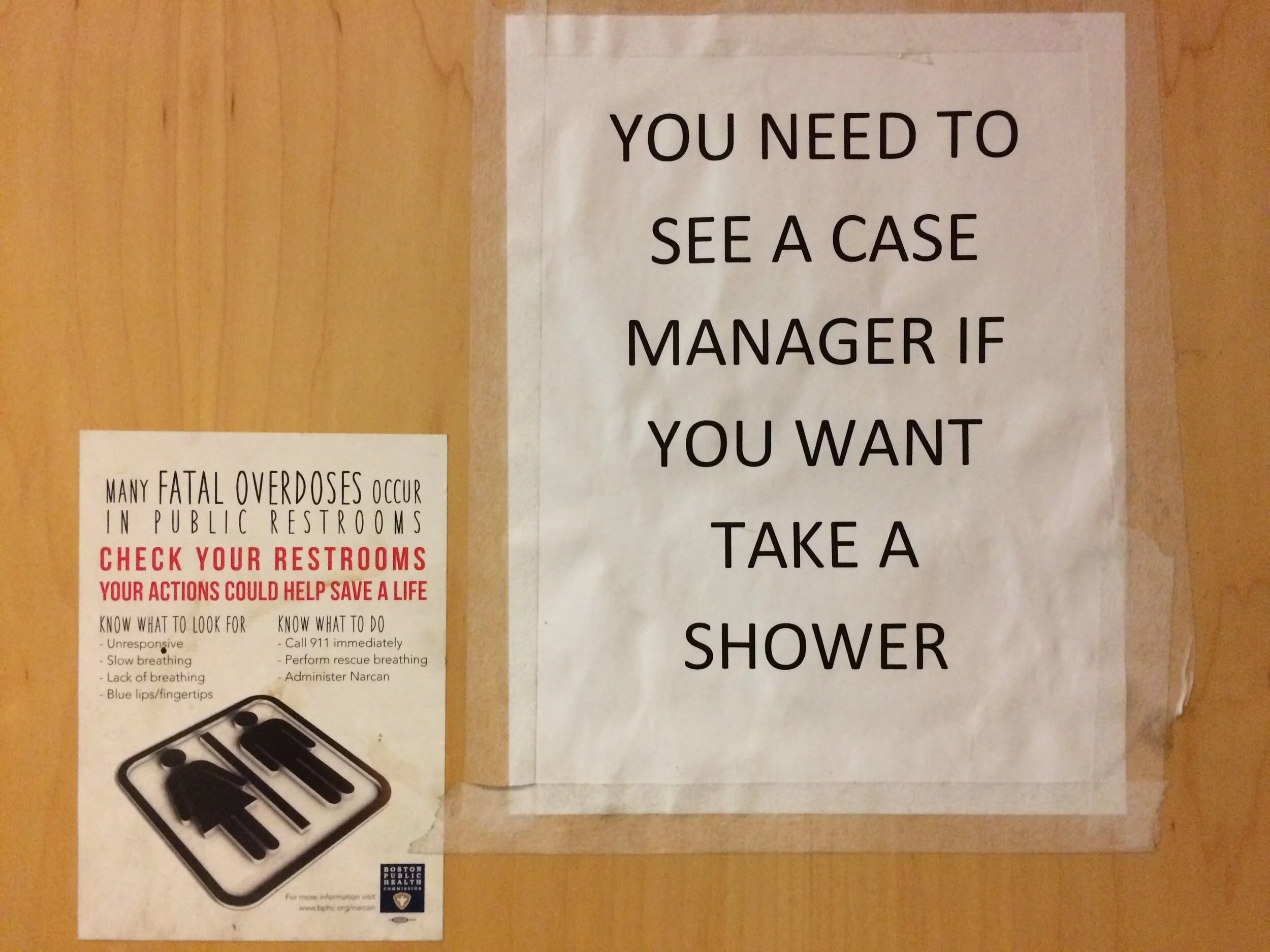

Right now, clinically, I fill mu-receptors. Or rather, I try to persuade people to fill their mu-receptors with a partial agonist that will block pure agonists. Simply making the effort to start people on buprenorphine is associated with a reduction in mortality of at least 50% in people with a prior non-fatal overdose in Massachusetts, people who have a startlingly high risk of death.

There’s more to it than that, of course, but I like this central and basic task for being concrete and useful. I would like to think that, if I make people register for something, and sign up, and wait to see me, well, I get them at least part of what they’re looking for.

And there is so much pain in people who shoot dope—it’s why they started doing it in the first place—that it can seem like the tears I cry are all about pain. But I know I’m better off when I’m not looking for tears from pain; but tears from beauty. I still find them, when I start making real connections to people; when they’re telling me things that are painful but they’re also sliding a joke in there; when we literally can laugh and cry together over time. I think of patients like that later, and—there it is. The Rule of Tears. I’m still where I’m supposed to be if that’s still there.

This is the spiritual meaning; this is the work. Not the substitution of one person’s pain for my own; but the mutual search for humanity, for some truth in our own experience and what we bring to each other, for a sense of purpose. And this won’t be just my purpose, or just theirs. It will be a combined sense of purpose that we will—starting with the task of figuring out how to swap in buprenorphine for street dope—try to find together.

I found it a couple of days ago. For whatever reason it had been a little while; maybe I’d been going through the motions. And then someone from a while ago showed up. And I can’t say the details. But we laughed. And could’ve cried, but didn’t right then. And, we just shared a common purpose, and we got it done, and it felt good to everyone involved. And I got a little bit teary afterwards, thinking about it. There. Rule of Tears.

* * *

If that Red Cross volunteer I still think of had any time or ability to get to know my wife and me on the night of the fire, even a little, we might have made him sad; but we would have probably made him laugh; and he would’ve seen our strength, too. He would know he wasn’t talking to victims, but to people with stories. Even if he couldn’t find a room for us and our cat, he could’ve at least laughed at our bitter jokes. And we could’ve been quiet together for a minute. And, even if all he’d done for us was to say, well, good luck, take care, I do think that if we thought he’d seen us for who we were, his presence could’ve meant something to us.

As it was, we suspected him of being some pre-med getting a cheap rush from going out in the middle of the night to a fire, and I don’t know what became of him, and to be honest he’s probably a perfectly nice person who just didn’t have a hotel room for people who didn’t really need it anyway. Traumatized people not infrequently read me as just a vampire who isn’t helping them. It probably happens to the best of us. But I hated him in that moment, so I’d like to think he’s an attending physician, in a field chosen for its prestige rather than any particular gift he brought to it, trying to fill his inner emptiness by writing cheap essays about how suffering people taught him what a special person he is.

Meanwhile—hey! let’s stop being such a little bitch, and start returning to our own true spiritual impulses!—this is a year that I assertively need to remind myself of why I’m here.

If I’m still following the Rule of Tears, I do find my tears amidst the pain; but it is not the pain itself I need to cry for. It’s the beauty. If I’m just crying for the pain, I probably need to go follow the Rule of Tears somewhere else. Somewhere more beautiful.