Trauma therapist, 1946-2023.

This site seems to lately be an obituary site. For my stepfather, then my father, and now my mother. In fact, I see now that I haven’t written anything here except two music posts (and another music post I deleted), since my father’s death. In retrospect, not coincidentally, this year has been a kind of stuck year, with lots in my head, but not as much coming out.

My mother and my father have not been together since I was four years old. So somehow it was completely unpredictable and shocking to me that their deaths would come so close together, less than a year apart, both unexpected.

My father’s death was different; as soon as the oncologist showed me the MRI I understood what was almost certainly going to happen; and then when the biopsy results came, what was certain to happen. It was terrible but it was understandable. There was a brief rally for a treatment that might buy him some more time; but the pace and slope of his decline was almost exactly what the oncologist had predicted would occur without treatment. It was horrible; and I’m revisiting its horror now, almost exactly a year later. But it was horrible in a particular way, and a knowable way.

My mother’s death came after a long struggle in the hospital, first on the regular floor and then in an ICU, a terrible irony in several respects. My mom at some point had said, “The problem with our healthcare system is we’ve got all of these old people in ICUs instead of spending that money on children!” She was prone to absolutist statements of this kind, though to her credit she would usually engage the nuance of my objections. I remember convincing her of what I’d learned as a medicine resident, and observed and talked about with my wife who is a critical care doctor: that you don’t know who’s going to survive when they enter, and yes, it doesn’t make sense to continue if you know someone’s certainly not going to survive, but, you rarely know for sure. So when do you stop? When do you decide that the time for death has arrived? Do you just devalue the lives of old people because of their proximity to life expectancy?

And that’s how it was with my mom. A certainty, then a hope, then a desperate yearning, that surely this would get better. I kept telling the doctors, who saw an ill and frail older woman, that until recently she’d been walking by the river for miles daily by the river, driving, paying all her bills. I hoped somehow that this meant she would therefore have the well-being to survive the blows of her mysterious but progressive lung inflammation. I hoped it would mean they wouldn’t give up on her.

This was countered by an inexorable march towards irreversible damage and then death. If I drew a line in my head—I was never able to bring myself to do it on paper—her oxygen requirement had a steady slope of increase that never was too dramatically different day by day, but was more or less relentless, more or less linear, and shockingly rapid by the scale of a lifetime. Even by the middle of the hospital admission, I could see where that line was headed. It was not a complex curve.

I’m not a denialist. With a doctor I trusted, I sort of ran my own family meetings, the one thing in the ICU I was good at as a resident. Before he could walk me through that family meeting pathway, I reviewed the data as I understood it, confirmed that my understanding was correct, related that to her values and who she was as a person, and made clear that I understood there was a time that we would declare it done. With people I didn’t have to keep searching for, my family meetings were conducted very efficiently, by me. I knew for a while that after the last thing was tried—something with a low chance of success—I was going to have to choose the moment to withdraw ventilator support and thereby choose her time of death. And I knew, when I finally made that decision, that it was the right one. But it was as horrible as you can imagine it would be.

I find it still too painful to rehash the hospital course; I have so much sadness and frustration, and anger which I don’t know how to properly target, about different parts of it. When I wrote her obituary, I suggested people should donate to any of three causes in her memory; one of them, without any ambivalence on my part, was the UC Davis Medical Center Nursing Recognition Fund. So, I can at least say my anger isn’t targeted at the nurses.

And at least one thing I know for sure is that I was so disappointed and angry about the doctors who I had to prod into rethinking the differential, and the plan, all through deferential language and indirect questions, all this “I wonder if…” “I am so appreciative of… but I mean, it’s probably just my worrying, but I just can’t help worrying about…”—that kind of managing other people’s pride and self-doubt that women do to try to influence prideful men all the time. It was absolutely exhausting and demoralizing, just like that version is for women. It infuriated my mother when people expected that of her. She performed that masquerade much less often than some people do, and was sometimes taken as startlingly blunt or confrontational as a result.

I was disappointed and angry most of all about some of the doctors who kept me at arm’s length, avoided talking to me, didn’t include me on rounds; even in some cases, seemed scared of talking to me. Obviously her care was not going well; judgment calls could have gone differently; I’m sure they doubted themselves or felt defensive about how they anticipated me judging them. Still, I have frank contempt for doctors who are unwilling to face their own self-doubt or share it with another physician. That all too familiar sad and infuriating charade. I was so grateful for the doctors who did that differently. Who simply talked to me and to my wife like doctors talking to each other, which is what my mother wanted and needed them to do.

My mother was proud of me, and in fact she was especially proud of me going to medical school and becoming a doctor, and marrying a doctor, and the way we made our lives as students and then doctors together. “I admire you,” she said, with emphasis, as I left to go back to Boston for the first time, before I returned, on the plane while she was being intubated.

But that thing? The doctors acting like Doctors instead of humans, talking down as a power strategy, talking confidently through the cracks and tears in their reasoning, blowing past personal particulars with generalized assumptions and fallacies? She hated that about doctors. She had always hated that so much.

* * *

I think, well surely there must have been some other month of my life that was worse than August to early September of 2023. There must have been, right? But right now, at least, I can’t think of one.

* * *

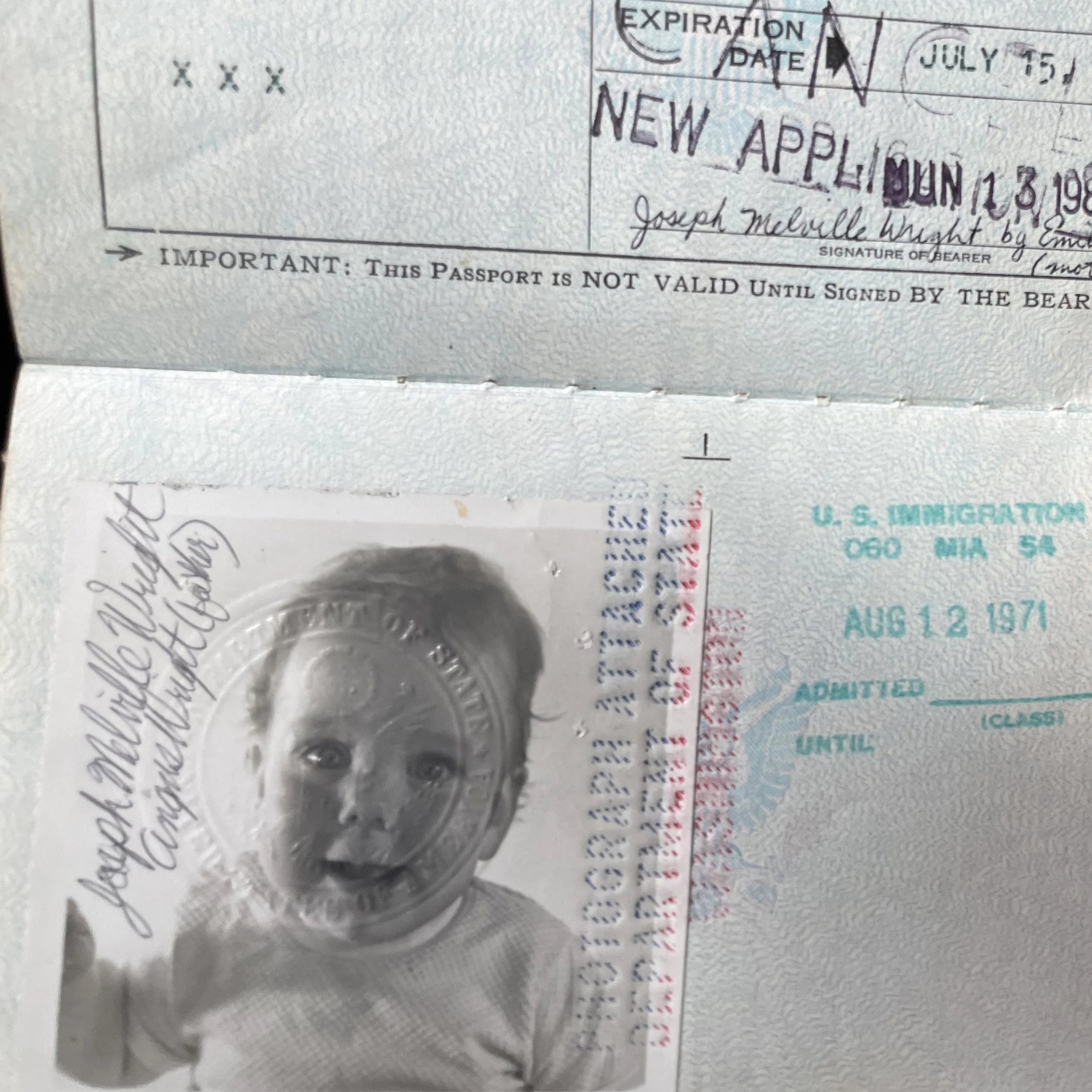

My baby passport, picture from 1970 I think.

Her passport, 1971; she was a young mother, 22 when I was born.

I probably need to write much more about her. To tell her story. But as I try, I find that I’m still too raw, too sad, too confused by my intense mix of emotions about this moment, to write more than a typical obituary, that hides much more than it reveals. But it at least states the basics:

Sacramento, California - Emily Mason Wright. A retired therapist, she died last month of an unexpected and rapidly progressive autoimmune condition. She was 76 years old.

She grew up in Salina, Kansas, spending much of her childhood and teenage years playing violin and finding comfort in the small but devoted bohemian and arts worlds of central Kansas. She attended the University of Kansas, worked as an air photo interpreter and cartographer, traveled and lived in Latin America, and became a mother.

After the end of her first marriage, she studied geography and history at California State University, Sacramento; and then later returned to CSUS for a master's degree in social work. She worked for many years as a therapist for child survivors of abuse, primarily at the Child and Family Institute; and provided clinical supervision for staff at Sacramento Self-Help Housing.

She was a poet, a devoted keeper of journals, a voracious reader, and as she put it recently, an "ardent feminist." She was a founding member of the La Semilla Cultural Center, and of the Sacramento Labor Chorus; and a volunteer docent for the California State Indian Museum. She walked many miles every week along the American River Parkway, and had a deep love and knowledge of the plants and animals of Northern California.

She is preceded in death by her husband, and life partner of more than four decades, Ernie Isaacs; as well as by her brother Peter. She is survived by her son Joe Wright and his wife Jen Stevens, and their daughter Lucy; as well as by her sister Molly Cooley, her brother John Mason; her nieces and nephews; and Ernie's children, grandchildren, and nephews. In lieu of flowers, consider donations to the California Indian Basketweavers' Association, the National Network of Abortion Funds, and/or the Nursing Recognition Fund of the UC Davis Medical Center.

I will say this. Once when I was a medical student, I went to a big multi-hospital palliative care case conference, and they presented the case of a “difficult” family. And they were really having a hard time in figuring out how to connect to and help this family. I don’t recall all the details and couldn’t say them even if I did; but the general summary was that they were intellectuals, clearly comprehending the medical details, and yet confronting the medical team all the time, battling them, distrusting them. More details. And they were absolutely baffled. Good case, they seemed to think; tough problem; hard to solve. Meanwhile, this was sounding more and more familiar.

Finally, I raised my hand. “I just have to say, this sounds exactly like my family.” I remember that the people in the big lecture hall all turned to me, like, truly startled. My mother, is what I really meant. “The reason they are behaving that way is that they see medicine as a system of power, and of patriarchy, and they do not trust that the system has their best interests at heart. They disagree with the whole political basis of the authority that the team is trying to exert. They’re part of a feminist tradition that explicitly rejects that. You’re asking them to trust you implicitly and that’s not on offer.” They seemed to find this revelatory, though I’m still not sure they were going to treat the patient differently.

Anyway, I will always remember that moment. Some angry Cambridge feminist with a dire medical problem, being presented to the hospital like a problem, by mostly women clinicians incidentally, as if they had never heard of the women’s health movement, as if they had never questioned the moral and political legitimacy of academic hospitals and their ilk, as if they just saw those politics as some kind of oddball smart-person psychological problem. As if they assumed that they were the Good People, and anyone who resisted was somehow missing that point.

Which is just one of the reasons, among many, that I am heartbroken not only about her death but about the fact that it happened in a hospital. Not that she was like that family in the case conference; for one thing, she was too quickly sick, and everyone was struggling to understand what was next. It was not the time she would have been outright battling her medical team. For another thing, she was relying on us. She traded that mode of feminist confrontation for trusting that at least these doctors—her family—would be sticking up for her, would see her as a whole person. I’m not sure it did any good. That trust is painful now.

I’m grateful, though, that the nurses acted through conscientiousness and kindness, generally not trying to impose power, seeing my mom for who she was. Especially in the ICU, they were calm and kind companions to my grief and worry. After all, as you realize when you sit with someone in the hospital day after day, even in the ICU, you barely see any doctors. Your relationships with doctors, in the long days of nothing happening for hours and hours, are mostly defined by the relationship of the suffering person’s body to decisions entered electronically in other rooms. Their orders.

UC Davis Medical Center, Sacramento, California. The hallway to the medical ICU.